DNA: molecular structure

Contributor(s)

| Written | 2006-09 | Jean-Loup Huret |

| Genetics, Dept Medical Information, University of Poitiers, CHU Poitiers Hospital, F-86021 Poitiers, France |

- I. Primary structure of the molecule:covalent backbone and bases aside

- Phosphoric acid

- Sugar

- Nitrogenous bases

- II. Secondary and tertiary structures of the molecule -Three-dimentional conformation of DNA

- Dinucleotides

- DNA molecule

- 2.1 Hydrogen bonds: bases pairin

- 2.2 Major groove and minor groove

- Non-B DNA

- 3.1 Z-DNA

- 3.2 Cruciform DNA and hairpin DNA

- H-DNA or triplex DNA

- G4-DNA

- DNA and mitochondria

- DNA denaturation

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) IS the genetic information of most living organisms (a contrario, some viruses, called retroviruses, use ribonucleic acid as genetic information).

- DNA can be copied over generations of cells: DNA replication

- DNA can be translated into proteins: DNA transcription into RNA, further translated into proteins ,

- DNA can be repaired when needed: DNA repair .

Ribonucleic acids (RNAs) are described in another chapter ( mRNA, r-RNA, t-RNA... )

- DNA is a polymere, made of units called nucleotides (or mononucleotides).

- Nucleotides also have other functions: (energy carriers: ATP, GTP; cellular respiration: NAD, FAD; signal transduction: cyclic AMP; coenzymes: CoA, UDP; vitamins: nicotinamide mononucleotide, Vit B2)

Using the protein nomenclature, we could speak in terms of primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary structures of the molecule:

I. Primary structure of the molecule:covalent backbone and bases aside

A nucleoside is made of a sugar + a nitrogenous base. A nucleotide is made of a phosphate + a sugar + a nitrogenous base. In DNA,the nucleotide is a deoxyribonucleotide (in RNA, the nucleotide is a ribonucleotide).

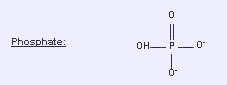

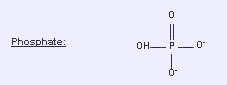

1.1.Phosphoric acid

Gives a phosphate group.

1.2.Sugar

Deoxyribose, which is a cyclic pentose (5-carbon sugar). Note: the sugar in RNA is a ribose. Carbons in the sugar are noted from 1 to 5. A nitrogen atom from the nitrogenous base links to C1 (glycosidic link), and the phosphate links to C5 (ester link) to make the nucleotide. The nucleotide is therefore: phosphate - C5 sugar C1 - base.

1.3.Nitrogenous bases

Aromatic heterocycles; there are purines and pyrimidines.

- Purines: adenine (A) and guanine (G).

- Pyrimidines: cytosine (C) and thymine (T) (Note: thymine is replaced by uracyle (U) in RNA).

Note: other nitrogenous bases exist, in particular methylated bases derived from the above mentioned; methylation of the bases has a functional role (see chapter ad hoc).

Glossary:

- Nucleoside names: deoxyribonucleosides in DNA: deoxyadenosine, deoxyguanosine, deoxycytidine, deoxythymidine in DNA (ribonucleosides in RNA: adenosine, guanosine, cytidine, uridine).

- Nucleotide names: deoxyribonucleotides in DNA: deoxyadenylic acid, deoxyguanylic acid, deoxycytidylic acid, deoxythymidylic acid (ribonucleotides in RNA: adenylic acid, guanylic acid, cytidylic acid, uridylic acid).

II. Secondary and tertiary structures of the molecule:

Three-dimentional conformation of DNA

2.1 Dinucleotides

Dinucleotides form from a phosphodiester link between 2 mononucleotides. The phosphate of a mononucleotide (in C5 of its sugar) being linked to the C3 of the sugar of the previous mononucleotide. Then, we start with a phosphate, a 5 sugar (+base) and the 3 of this sugar, linked to a second phosphate - 5 sugar, which 3 is free for next step. The link -and the orientation of the molecule- is therefore 5 -> 3. Polynucleotides are made of the successive addition of monomeres in a general 5 -> 3 configuration. The backbone of the molecule is made of a succession of phosphate-sugar (nucleotide n) - phosphate-sugar (nucleotide n+1), and so on, covalently linked, the bases being aside.

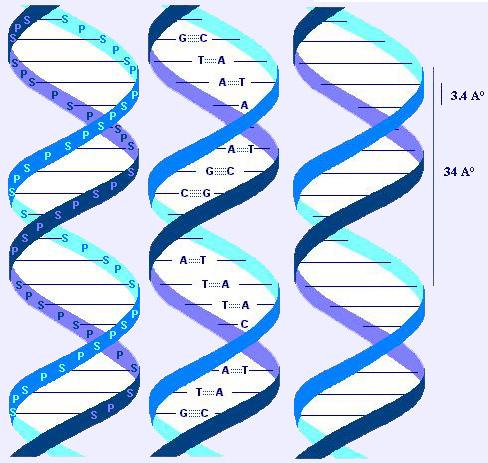

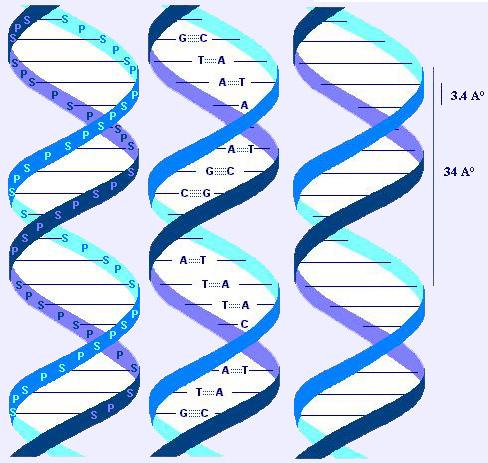

2.2 DNA molecule

DNA is made of two ("duplex DNA") dextrogyre (like a screw; right-handed) helical chains or strands ("the double helix"), coiled around an axis to form a double helix of 20A° of diameter. The two strands are antiparallel (id est: their 5->3 orientations are in opposite direction). The general appearance of the polymere shows a periodicity of 3.4 A°, corresponding to the distance between 2 bases, and another one of 34 A°, corresponding to one helix turn (and also to 10 bases pairs).

2.2.1 Hydrogen bounds: bases pairing

The (hydrophobic) bases are stacked on the inside, there planes are perpendicular to the axis of the double helix. The outside (phosphate and sugar) are hydrophilic.

Hydrogen bounds between the bases of one strand and that of the other strand hold the two strands together (dashed lines in the drawing).

A purine on one strand shall link to a pyrimidine on the other strand. As a corollary, the number of purines residues equals the number of pyrimidine residues.

A binds T (with 2 hydrogen bounds).

G binds C (with 3 hydrogen bounds: more stable link: 5.5 kcal vs 3.5 kcal).

Note: the content in A in the DNA is therefore equal to the content in T, and the content in G equals the content in C.

This strict correspondance (A<->T and G<->C) makes the 2 strands complementary. One is the template of the other one, and reciprocally: this property will allow exact replication (semi-conservative replication: one strand -the template- is conserved, another is newly synthesized, same with the second strand, conserved, allowing another one to be newly synthesized; see chapter ad hoc).

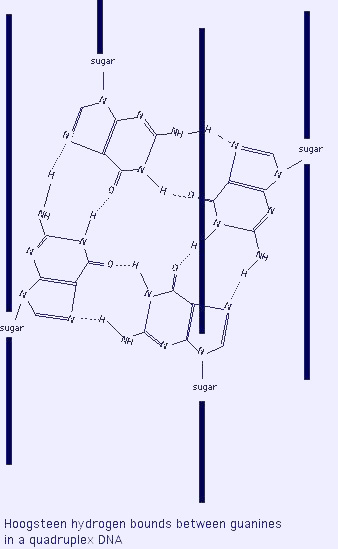

Note: Hydrogen bounds in base pairing are sometimes different from the model of Watson and Crick above described, using the N7 atom of the purine instead of the N1 (Hoogsteen model).

2.2.2 Major groove and minor groove

The double helix is a quite rigid and viscous molecule of an immense length and a small diameter. It presents a major groove and a minor groove.

The major groove is deep and wide, the minor groove is narrow and shallow.

DNA-protein interactions are major/essential processes in the cell life (transcription activation or repression, DNA replication and repair).

Proteins bind at the floor of the DNA grooves, using specific binding: hydrogen bounds, and non specific binding: van der Waals interactions, generalized electrostatic interactions; proteins recognize H-bond donnors, H-bond acceptors, metyl groups (hydrophobic), the later being exclusively in the major groove; there are 4 possible patterns of recognition with the major groove, and only 2 with the minor groove (see iconography).

Some proteins bind DNA in its major groove, some other in the minor groove, and some need to bind to both.

Note:

- The 2 strands are called "plus" and "minus" strands, or "direct" and "reverse" strands. At a given location where one strand (any of the two) bears coding sequences, it is unlikely (but not impossible) that the other strand also bears coding sequences.

- DNA is ionized in vivo and behave like a polyanion.

The double helix as described above is the "B" form of the DNA; it is the form the most commonly found in vivo, but other forms exist in vivo (see below) or in vitro. The "A" form resemble B-DNA but it is less hydrated than B-DNA, "A" form is not found in vivo.

2.3 Non-B DNA

DNA is a molecule which moves, fidgets, does gymnastics, dances. The structures below cited are being proved to have funtional roles; on the other hand, they may favour DNA breaks and further deletions, amplification, recombination, and mutations.

Glossary:

Palindromes: these are names that read the same backwards and forwards (e.g. "DNA LAND"). DNA uses to play with palindromes (see below).

2.3.1 Z-DNA

- Z form is a levogyre (left handed) double helix with a zig-zag conformation of the backbone (less smooth than B-DNA). Only one groove is observed, resembling the minor groove, the base pairs being set off to the side, far from the axis. The bases (which form the major groove -close to the axis- in B-DNA) are here at the outer surface. Phosphates are closer together than in B-DNA. Z-DNA cannot form nucleosomes.

- A high G-C content favours Z conformation. Cytosine methylation, and molecules which can be present in vivo such as spermine and spermidine can stabilize Z conformation.

- DNA sequences can flip from a B form to a Z form and vice versa: Z-DNA is a transient form in vivo.

- Z-DNA formation occurs during transcription of genes, at transription start sites near promoters of actively transcribed genes. During transcription, the movement of RNA polymerase induces negative supercoiling upstream and positive supercoiling downstream the site of transcription The negative supercoiling upstream favours Z-DNA formation; a Z-DNA function would be to absorb negative supercoiling. At the end of transcription, topoisomerase relaxes DNA back to B conformation.

- Certain proteins bind to Z-DNA, in particular double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminase (ADAR1), a Z-DNA binding nuclear-RNA-editing enzyme; this enzyme converts adenine to inosine in the pre-mRNA. Following, ribosomes will interpret inosine as guanine, and the protein coded with this epigenetic modification will be different (see chpater on Epigenetics).

Note:

- Z-DNA antibodies are found in lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases.

- Double stranded RNA (dsRNA) can adopt a Z conformation.

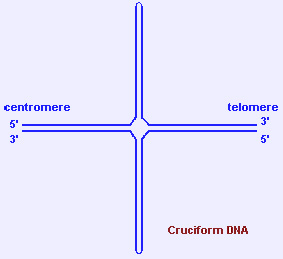

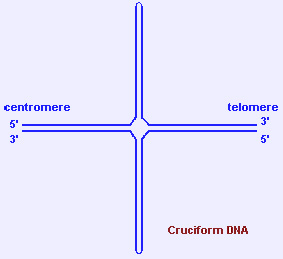

2.3.2 cruciform DNA and hairpin DNA

- Holliday junctions (formed during recombination) are cruciform structures. Inverted (or mirror) repeats (palindromes) of polypurine/polypyrimidine DNA stretches can also form cruciform or hairpin structures through intra-strand pairing.

- Palindromic AT-rich repeats are found at the breakpoints of the t(11;22)(q23;q11), the only known recurrent constitutional reciprocal translocation.

- Nucleases bind and cleave holliday junctions after recombination. Other well known proteins such as HMG proteins and MLL (for further reading, see: MLL) can also bind cruciform DNA.

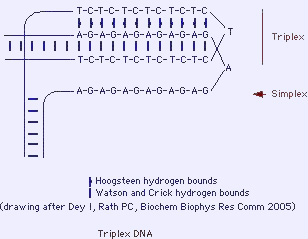

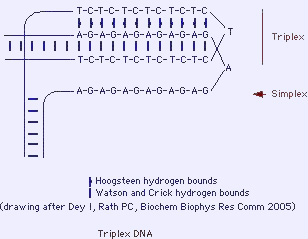

2.3.3 H-DNA or triplex DNA

- Inverted repeats (palindromes) of polypurine/polypyrimidine DNA stretches can form triplex structures (triple helix). A triple-stranded plus a single stranded DNA are formed.

- H-DNA may have a role in functional regulation of gene expression as well as on RNAs (e.g. repression of transcription).

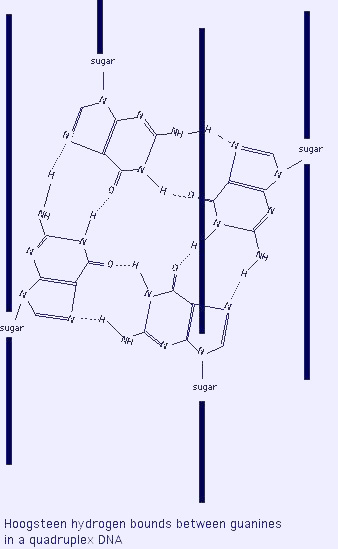

2.3.4 G4-DNA

- G4 DNA or quadruplex DNA: folding of double stranded GC-rich sequence onto itself forming Hoogsteen base pairing between 4 guanines ("G4"), a highly stable structure. Often found near promotors of genes and at the telomeres.

- Role in meiosis and recombination; may be regulatory elements.

- RecQ family helicases are able to unwind G4 DNA (e.g. BLM, the gene mutated in Bloom syndrome (for further reading, see: Bloom syndrome)).

III. Quaternary structure of the molecule - Chromatin

DNA is associated with proteins: histones and non histone proteins, to form the chromatin. DNA as a whole is acidic (negatively charged) and binds to basic (positively charged) proteins called histones: see chapter Chromatin.

There is 3 x 10 9 nucleotide pairs in the human haploid genome representing about 30 000 genes dispersed over 23 chromosomes for an haploid set.

IV. Various

4.1 DNA and mitochondria

See also Mitochondrial inheritance

- DNA is found in the nucleus of the cell, but a small amount is also present in the mitochondria.

- Mitochondrias would originate from archeobacterias which became endosymbiotic to eukaryotic cells.

- Their genetic code is different from the so-called "universal" code (UGA, AUA, AGA, AGG: respectively STOP, Ile, Arg, Arg in the universal code, and Trp, Met, STOP, STOP in the mitochondria of mammals, and other meanings in mitochondria of other spieces).

- The number of DNA copies in one given mitochondria is variable.

- Mitochondrial DNA is circular, with a heavy and a light chains, has no introns, not any non-coding sequence.

- Genes from the mitochondria code for proteins involved in electron transport, ribosomic RNAs (rRNAs), and transfer RNAs (tRNAs).

- Each DNA strand is transcribed, then cut into the mRNAs, but also into rRNAs and tRNAs.

Note:

The mitochondria also use proteins imported from the cytoplasm of the cell (and coded by the nucleus); so far, proteins from the mitochondria are not exported into the cytoplasm except in case of apoptosis.

4.2 DNA denaturation

The double helix undergoes unwinding in vitro with heat, extremes ph, and other conditions (urea, ...). A melting point can be calculated; it is characteristic of the A/T versus G/C proportion of the specimen studied, due to the fact that there is only 2 hydrogen bounds in A/T, and 3 in G/C, a more stable binding. Upon denaturation, the physical properties of the DNA change; e.g. hyperchromic effect: light absorption at 260 nm is higher with denatured DNA than with double standed DNA. Light absorption also varies according to the A/T vs G/C proportion: it is higher in A/T rich specimens than in G/C rich ones.

DNA denaturation is to be known, because:

- it allows to measure A/T vs G/C content

- it is the basis of in situ hybridization techniques (see Methods in Genetics)

I. Primary structure of the molecule:covalent backbone and bases aside

A nucleoside is made of a sugar + a nitrogenous base. A nucleotide is made of a phosphate + a sugar + a nitrogenous base. In DNA,the nucleotide is a deoxyribonucleotide (in RNA, the nucleotide is a ribonucleotide).

1.1.Phosphoric acid

Gives a phosphate group.

1.2.Sugar

Deoxyribose, which is a cyclic pentose (5-carbon sugar). Note: the sugar in RNA is a ribose. Carbons in the sugar are noted from 1 to 5. A nitrogen atom from the nitrogenous base links to C1 (glycosidic link), and the phosphate links to C5 (ester link) to make the nucleotide. The nucleotide is therefore: phosphate - C5 sugar C1 - base.

1.3.Nitrogenous bases

Aromatic heterocycles; there are purines and pyrimidines.

- Purines: adenine (A) and guanine (G).

- Pyrimidines: cytosine (C) and thymine (T) (Note: thymine is replaced by uracyle (U) in RNA).

Note: other nitrogenous bases exist, in particular methylated bases derived from the above mentioned; methylation of the bases has a functional role (see chapter ad hoc).

Glossary:

- Nucleoside names: deoxyribonucleosides in DNA: deoxyadenosine, deoxyguanosine, deoxycytidine, deoxythymidine in DNA (ribonucleosides in RNA: adenosine, guanosine, cytidine, uridine).

- Nucleotide names: deoxyribonucleotides in DNA: deoxyadenylic acid, deoxyguanylic acid, deoxycytidylic acid, deoxythymidylic acid (ribonucleotides in RNA: adenylic acid, guanylic acid, cytidylic acid, uridylic acid).

II. Secondary and tertiary structures of the molecule:

Three-dimentional conformation of DNA

2.1 Dinucleotides

Dinucleotides form from a phosphodiester link between 2 mononucleotides. The phosphate of a mononucleotide (in C5 of its sugar) being linked to the C3 of the sugar of the previous mononucleotide. Then, we start with a phosphate, a 5 sugar (+base) and the 3 of this sugar, linked to a second phosphate - 5 sugar, which 3 is free for next step. The link -and the orientation of the molecule- is therefore 5 -> 3. Polynucleotides are made of the successive addition of monomeres in a general 5 -> 3 configuration. The backbone of the molecule is made of a succession of phosphate-sugar (nucleotide n) - phosphate-sugar (nucleotide n+1), and so on, covalently linked, the bases being aside.

2.2 DNA molecule

DNA is made of two ("duplex DNA") dextrogyre (like a screw; right-handed) helical chains or strands ("the double helix"), coiled around an axis to form a double helix of 20A° of diameter. The two strands are antiparallel (id est: their 5->3 orientations are in opposite direction). The general appearance of the polymere shows a periodicity of 3.4 A°, corresponding to the distance between 2 bases, and another one of 34 A°, corresponding to one helix turn (and also to 10 bases pairs).

2.2.1 Hydrogen bounds: bases pairing

The (hydrophobic) bases are stacked on the inside, there planes are perpendicular to the axis of the double helix. The outside (phosphate and sugar) are hydrophilic.

Hydrogen bounds between the bases of one strand and that of the other strand hold the two strands together (dashed lines in the drawing).

A purine on one strand shall link to a pyrimidine on the other strand. As a corollary, the number of purines residues equals the number of pyrimidine residues.

A binds T (with 2 hydrogen bounds).

G binds C (with 3 hydrogen bounds: more stable link: 5.5 kcal vs 3.5 kcal).

Note: the content in A in the DNA is therefore equal to the content in T, and the content in G equals the content in C.

This strict correspondance (A<->T and G<->C) makes the 2 strands complementary. One is the template of the other one, and reciprocally: this property will allow exact replication (semi-conservative replication: one strand -the template- is conserved, another is newly synthesized, same with the second strand, conserved, allowing another one to be newly synthesized; see chapter ad hoc).

Note: Hydrogen bounds in base pairing are sometimes different from the model of Watson and Crick above described, using the N7 atom of the purine instead of the N1 (Hoogsteen model).

2.2.2 Major groove and minor groove

The double helix is a quite rigid and viscous molecule of an immense length and a small diameter. It presents a major groove and a minor groove.

The major groove is deep and wide, the minor groove is narrow and shallow.

DNA-protein interactions are major/essential processes in the cell life (transcription activation or repression, DNA replication and repair).

Proteins bind at the floor of the DNA grooves, using specific binding: hydrogen bounds, and non specific binding: van der Waals interactions, generalized electrostatic interactions; proteins recognize H-bond donnors, H-bond acceptors, metyl groups (hydrophobic), the later being exclusively in the major groove; there are 4 possible patterns of recognition with the major groove, and only 2 with the minor groove (see iconography).

Some proteins bind DNA in its major groove, some other in the minor groove, and some need to bind to both.

Note:

- The 2 strands are called "plus" and "minus" strands, or "direct" and "reverse" strands. At a given location where one strand (any of the two) bears coding sequences, it is unlikely (but not impossible) that the other strand also bears coding sequences.

- DNA is ionized in vivo and behave like a polyanion.

The double helix as described above is the "B" form of the DNA; it is the form the most commonly found in vivo, but other forms exist in vivo (see below) or in vitro. The "A" form resemble B-DNA but it is less hydrated than B-DNA, "A" form is not found in vivo.

2.3 Non-B DNA

DNA is a molecule which moves, fidgets, does gymnastics, dances. The structures below cited are being proved to have funtional roles; on the other hand, they may favour DNA breaks and further deletions, amplification, recombination, and mutations.

Glossary:

Palindromes: these are names that read the same backwards and forwards (e.g. "DNA LAND"). DNA uses to play with palindromes (see below).

2.3.1 Z-DNA

- Z form is a levogyre (left handed) double helix with a zig-zag conformation of the backbone (less smooth than B-DNA). Only one groove is observed, resembling the minor groove, the base pairs being set off to the side, far from the axis. The bases (which form the major groove -close to the axis- in B-DNA) are here at the outer surface. Phosphates are closer together than in B-DNA. Z-DNA cannot form nucleosomes.

- A high G-C content favours Z conformation. Cytosine methylation, and molecules which can be present in vivo such as spermine and spermidine can stabilize Z conformation.

- DNA sequences can flip from a B form to a Z form and vice versa: Z-DNA is a transient form in vivo.

- Z-DNA formation occurs during transcription of genes, at transription start sites near promoters of actively transcribed genes. During transcription, the movement of RNA polymerase induces negative supercoiling upstream and positive supercoiling downstream the site of transcription The negative supercoiling upstream favours Z-DNA formation; a Z-DNA function would be to absorb negative supercoiling. At the end of transcription, topoisomerase relaxes DNA back to B conformation.

- Certain proteins bind to Z-DNA, in particular double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminase (ADAR1), a Z-DNA binding nuclear-RNA-editing enzyme; this enzyme converts adenine to inosine in the pre-mRNA. Following, ribosomes will interpret inosine as guanine, and the protein coded with this epigenetic modification will be different (see chpater on Epigenetics).

Note:

- Z-DNA antibodies are found in lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases.

- Double stranded RNA (dsRNA) can adopt a Z conformation.

2.3.2 cruciform DNA and hairpin DNA

- Holliday junctions (formed during recombination) are cruciform structures. Inverted (or mirror) repeats (palindromes) of polypurine/polypyrimidine DNA stretches can also form cruciform or hairpin structures through intra-strand pairing.

- Palindromic AT-rich repeats are found at the breakpoints of the t(11;22)(q23;q11), the only known recurrent constitutional reciprocal translocation.

- Nucleases bind and cleave holliday junctions after recombination. Other well known proteins such as HMG proteins and MLL (for further reading, see: MLL) can also bind cruciform DNA.

2.3.3 H-DNA or triplex DNA

- Inverted repeats (palindromes) of polypurine/polypyrimidine DNA stretches can form triplex structures (triple helix). A triple-stranded plus a single stranded DNA are formed.

- H-DNA may have a role in functional regulation of gene expression as well as on RNAs (e.g. repression of transcription).

2.3.4 G4-DNA

- G4 DNA or quadruplex DNA: folding of double stranded GC-rich sequence onto itself forming Hoogsteen base pairing between 4 guanines ("G4"), a highly stable structure. Often found near promotors of genes and at the telomeres.

- Role in meiosis and recombination; may be regulatory elements.

- RecQ family helicases are able to unwind G4 DNA (e.g. BLM, the gene mutated in Bloom syndrome (for further reading, see: Bloom syndrome)).

III. Quaternary structure of the molecule - Chromatin

DNA is associated with proteins: histones and non histone proteins, to form the chromatin. DNA as a whole is acidic (negatively charged) and binds to basic (positively charged) proteins called histones: see chapter Chromatin.

There is 3 x 10 9 nucleotide pairs in the human haploid genome representing about 30 000 genes dispersed over 23 chromosomes for an haploid set.

IV. Various

4.1 DNA and mitochondria

See also Mitochondrial inheritance

- DNA is found in the nucleus of the cell, but a small amount is also present in the mitochondria.

- Mitochondrias would originate from archeobacterias which became endosymbiotic to eukaryotic cells.

- Their genetic code is different from the so-called "universal" code (UGA, AUA, AGA, AGG: respectively STOP, Ile, Arg, Arg in the universal code, and Trp, Met, STOP, STOP in the mitochondria of mammals, and other meanings in mitochondria of other spieces).

- The number of DNA copies in one given mitochondria is variable.

- Mitochondrial DNA is circular, with a heavy and a light chains, has no introns, not any non-coding sequence.

- Genes from the mitochondria code for proteins involved in electron transport, ribosomic RNAs (rRNAs), and transfer RNAs (tRNAs).

- Each DNA strand is transcribed, then cut into the mRNAs, but also into rRNAs and tRNAs.

Note:

The mitochondria also use proteins imported from the cytoplasm of the cell (and coded by the nucleus); so far, proteins from the mitochondria are not exported into the cytoplasm except in case of apoptosis.

4.2 DNA denaturation

The double helix undergoes unwinding in vitro with heat, extremes ph, and other conditions (urea, ...). A melting point can be calculated; it is characteristic of the A/T versus G/C proportion of the specimen studied, due to the fact that there is only 2 hydrogen bounds in A/T, and 3 in G/C, a more stable binding. Upon denaturation, the physical properties of the DNA change; e.g. hyperchromic effect: light absorption at 260 nm is higher with denatured DNA than with double standed DNA. Light absorption also varies according to the A/T vs G/C proportion: it is higher in A/T rich specimens than in G/C rich ones.

DNA denaturation is to be known, because:

- it allows to measure A/T vs G/C content

- it is the basis of in situ hybridization techniques (see Methods in Genetics)

Citation

Huret JL

Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology 2006-09-01

DNA: molecular structure

Online version: http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/teaching/30001/dna-molecular-structure